In 2018, my lab group, collaborators, and I were on a research ship at sea as a hurricane rapidly intensified to a Category 4. After several rolling days carefully avoiding the storm, we subsequently sampled directly in its wake—which to our knowledge no one has done before—providing completely new insights into the effects of hurricanes (tropical cyclones) on the ocean. Please read our paper in Science Advances to learn what we found! We also received press coverage in English (e.g., Discover) and Spanish (e.g., Mundiario). This is (briefly) how it happened…

Above: animation of hurricanes and satellite-sensed chlorophyll concentrations in the eastern Pacific in summer 2018. Hurricane Bud is the large storm in mid June (dates in bottom left corner). Warmer colors indicate more chlorophyll; note the big red/yellow spot left by Bud! (Black regions are gaps in the satellite coverage.)

We had a research expedition to the eastern tropical Pacific (the area off Mexico and Central America) planned for June 9-25, 2018, with the aim of capturing seasonal variations in this important area of the ocean. Obviously we hoped to dodge the start of hurricane season, but conditions were ripe for hurricane development—including hot sea surface temperatures of 32 degrees C, or nearly 90 degrees F. Thanks to science and technology, we knew early and accurately that a hurricane would develop—as well as when, where, and how things might change. So we had a plan (and a backup plan, and a backup to that) that was put in motion after a tweet from the National Hurricane Center (NHC) flapped its wings:

We left the port of Mazatlán knowing that we had a day or two to conduct the first part of our research. The heat was overwhelming the ship’s AC, other than the area right near the computer racks, where we huddled to stay cool. I was working at a lab bench only a few feet away, yet sweating so much that it ran down my arms and filled my nitrile gloves. On day 2, we winched up sediment from the bottom of the ocean and then lashed everything down; the ship was already rolling from distant swells and the wind whipping. Our plan was to go closer to shore and steam back and forth behind some small islands (the Islas Marías) off the coast of Mexico, which would protect us from the storm’s worst swells. We spent many hours riding a disorganized slop of hot tub seawater (obviously many scientists and even some crew were sick):

The storm was named Hurricane Bud. Bud rapidly intensified like many recent storms because the ocean is so warm. Bud slowed down due to a lack of steering winds. Bud lived down its name. On the charts on the ship’s bridge, there was a red box where we would not go, updated every few hours. The captain had many years at sea and was adamant that you ‘never let a storm between you and shore, or it can chase you halfway across the ocean.’ If the storm turned our way, we would head into port.

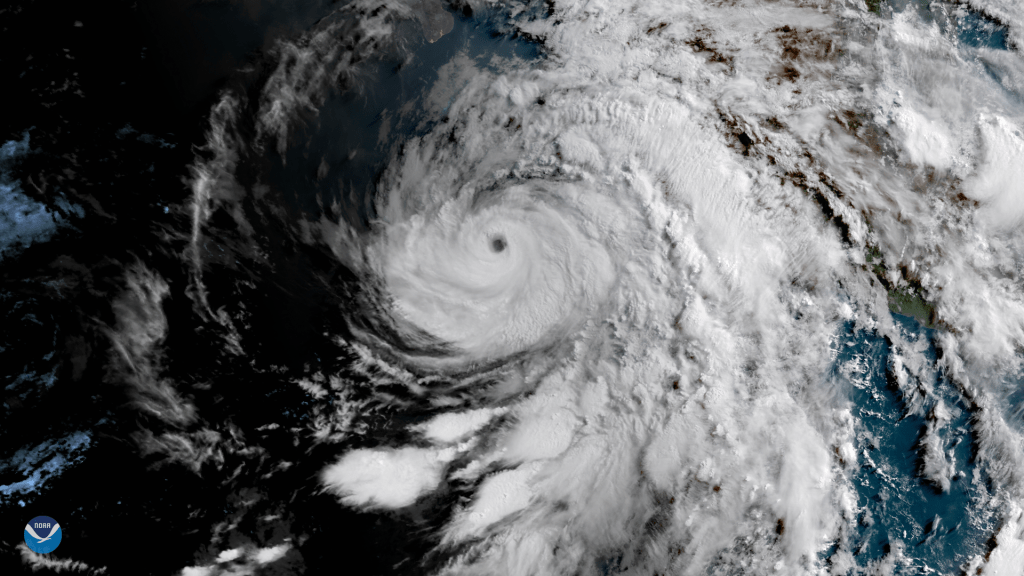

That didn’t happen, and we always felt safe on the R/V Oceanus thanks to Oregon State Marine Ops (honestly, thank you!). The satellite image above shows the massive size of the storm (the tip of the Baja peninsula looks puny at the top of the image) and we were under the clouds to the northeast. We endured, and like an old sea tale, the storm passed, the sun came out, and the sea calmed. (There is a reason for this, which is that tropical cyclones act like a giant release valve for tropical ocean heat.) Some of the most serene days I’ve seen at sea:

We spent a week conducting our planned research, but as we turned north, I decided to add an extra sampling location. I thought this was on the border between two interesting parts of the region we were sampling, and that it looked close to the previous path of the hurricane… When we arrived in the early morning, you could see and even smell the difference. Fog formed over colder, visibly green water. We sniffed biologically-produced gases rising from the sea surface. We didn’t know for sure at the time, but we had entered the wake of the storm from a week before. We were just a few kilometers from Bud’s former eye position when it was near maximum intensity. The powerful winds had churned up deep, cold, nutrient-rich water that was fueling biological activity visible from satellites—that’s the animation above; notice the biological traces left by hurricanes. But due to the unique experience of being on a ship at sea, we discovered far more about the biological and chemical effects of tropical cyclones (hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones are known scientifically as tropical cyclones). We found at least 5 interesting things:

1. Although blooms of photosynthetic organisms (phytoplankton) have been observed in tropical cyclone wakes before, this is almost entirely from satellite; being on the water, we directly measured a more intense bloom than detected by satellite—indicating that we are underestimating the global importance of these cyclone-driven blooms.

2. Using a special technique, we were able to measure the full diversity of carbon compounds synthesized by blooming phytoplankton. This shows a clear imprint and effect on the carbon cycle.

3. We also found a bacterial ‘bloom’ of organisms responding to all of this carbon. In other words, hurricanes produce a feast for other organisms, including marine bacteria.

4. However, we also detected rapid shoaling of the low oxygen water found in this region (our whole reason for being there in the first place). These are the most profound changes in oxygen profiles that I have seen anywhere, anytime, and place anoxic water very close to the surface.

5. Finally, we found that the sampling station we added is actually THE hurricane hotspot in the eastern Pacific Ocean…. read our Science Advances paper for more!

Taking a step back, we are logically worried about these storms when they reach land, and I don’t want to minimize the loss of life and property. But tropical cyclones form over and are fueled by the ocean, and (for obvious reasons) we know very little about what happens during storms at sea. We are learning more through drones, sensors, satellites, and chance occurrences like our own. This is pivotal because the oceans trap the vast majority of heat that builds up on the planet due to climate change. What we rocked—hurricane development, rapid intensification, and slowing forward speed—are becoming hallmarks of tropical cyclones in a warming ocean. Our work shows that they also disrupt ocean biology and chemistry, and are especially important in the eastern Pacific. Every year, hurricanes trace ghostly wakes where they’ve blended the upper ocean. Few people study these. Our group below was lucky/unlucky to do so. Stay tuned for more to come!